Residential Schools – Talking Points

Talking to kids about residential schools can be challenging but important. This guide offers supportive talking points to help parents start natural and meaningful conversations.

We deeply respect that there are diverse perspectives and valid interpretations surrounding this topic, and we firmly believe in your right as a parent to impart knowledge and values in the manner you deem most appropriate for your children. These posts are merely a supportive resource, crafted to empower you to facilitate meaningful discussions around this topic.

A long time ago in Canada, the government offered schooling for Indigenous children but since they lived in remote locations, many had to leave their homes and families to go to school. These schools were called residential schools. They were run by churches and operated from the 1870s until the 1990s. In 1920, it was mandated that all children between the ages of 7-16 had to go to school.

At these schools, Indigenous children were not allowed to speak their own languages or practice their traditions. They were told to speak English or French and follow European ways of life.

The children were often lonely or scared. Some children were treated badly at these schools. Today, many adults who went to residential schools as children—called survivors—have shared their stories. These stories are important because they help us learn what happened and how it made people feel. Many people believe these schools tried to erase Indigenous cultures, which caused great pain.

Some people say we should look at all parts of the story and life for all children, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, in this time frame. Many children across Canada lived hard lives. Schools were very strict, many children got sick from diseases like tuberculosis and many immigrants who came to Canada for a new life lived in very poor conditions without good housing or enough food. This helps us realize that life was very hard for many children in the early days of Canada.

It doesn’t mean we ignore the hurt that was caused in residential schools. We can care about survivors’ feelings while also trying to understand all the facts. We should always ask good questions and look for real evidence when we hear new things.

Not every residential school was the same. Some children learned useful things, and some teachers were kind. But many children were deeply hurt, and that must be remembered.

Learning about residential schools helps us understand what went wrong and how we can do better in the future. We must listen to survivors, respect different voices, and always look for the truth with kind and open hearts.

Residential schools are an important part of Canada’s history. These schools were created by the government and run by churches from the 1870s until the 1990s. During that time, about 150,000 Indigenous children attended these schools. In 1920, it was mandated that all children between the ages of 7-16 had to go to school.

The goal of residential schools was to teach Indigenous children English or French and make them follow European ways of life. But to do that, the children were often forced to stop speaking their own languages and practicing their cultures. Many children were separated from their families for months, or even years. Some were treated badly. Survivors of these schools have shared powerful stories about how painful those experiences were. Many people today believe the schools were part of something called cultural genocide—an attempt to erase Indigenous cultures.

While it’s important to listen to survivors and understand how harmful these schools were, some people also ask questions about how we tell the story of residential schools. They believe it’s important to look at all the facts, even the difficult ones. For example, they point out that schools long ago—whether Indigenous or not—were very different from schools today. Many children back then faced hard times, including poverty, disease, and strict punishments, whether they were in residential schools or not.

Some people also wonder if today’s discussions about residential schools are always fair. They are concerned that only one side of the story is being told, and that people who ask questions may be unfairly labeled as hateful or wrong. These people believe we should still ask for strong evidence when we hear big claims—like stories about mass graves—while always treating survivors and their stories with kindness and respect.

Good thinking means being able to do two things at once: we must listen carefully to those who were hurt by residential schools, and also think clearly about the facts. Not every school was the same. Not every child had the exact same experience. And not every teacher or worker was cruel. Some people believe the schools completely failed Indigenous communities. Others believe that even though the schools were flawed and harmful, they also gave some children a chance to learn reading, writing, and other skills.

In the end, learning about residential schools helps us understand both the mistakes of the past and how we can make things better in the future. We should always show respect, ask good questions, and work toward truth and reconciliation.

The legacy of residential schools in Canada is one of the most emotionally charged and complex issues in the country’s history. These institutions, operated from the 1870s until the 1990s, were government-funded and largely administered by Christian churches. Approximately 150,000 Indigenous children were placed in these schools under policies intended to assimilate them into Euro-Canadian culture. Many survivors recount experiences of cultural erasure, forced separation from family, and physical or emotional abuse.

Survivor testimony is essential to understanding the full impact of the residential school system. The stories of loss, trauma, and resilience have illuminated what many scholars and Indigenous leaders describe as cultural genocide—a systematic attempt to destroy Indigenous languages, traditions, and identities.

At the same time, critical historical inquiry requires the inclusion of multiple perspectives and a willingness to examine complex truths. While acknowledging the suffering endured by many, some historians argue that the schools were a reflection of the broader, assimilationist ideologies of the time rather than an explicit campaign of extermination (Milloy, 1999). This perspective suggests that the harms inflicted, while severe, were part of a broader set of institutional failures that affected both Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations during that era—including poor public health infrastructure, limited access to education, harsh disciplinary practices, and widespread poverty.

This raises important questions about how the narrative of residential schools has evolved in public discourse. Some critics argue that the prevailing narrative has become politicized, wherein certain perspectives are amplified while others are dismissed or even censored. Allegations of “denialism” are sometimes used to discredit individuals who seek to examine the historical record more critically, including calls for more rigorous evidence regarding claims of mass graves at former residential school sites. While sensitivity to survivor experiences is paramount, the pursuit of truth also requires careful evaluation of all available evidence—archival, archaeological, and forensic.

Engaging in critical thinking does not mean diminishing the suffering of survivors or denying the existence of abuse. Rather, it means approaching the subject with intellectual honesty: recognizing that not all residential schools were identical, not every staff member was abusive, and not every student had a uniformly negative experience.

The legacy of residential schools remains a painful chapter in Canadian history. A balanced, respectful approach is necessary—one that upholds the dignity of survivors while fostering open, evidence-based discussion. Some may view the residential school system as an unmitigated moral and policy failure; others may argue that, while deeply flawed, it also represented an attempt—however misguided—to provide education and integration. These perspectives are not mutually exclusive but should be understood as part of an ongoing dialogue about reconciliation, responsibility, and historical truth.

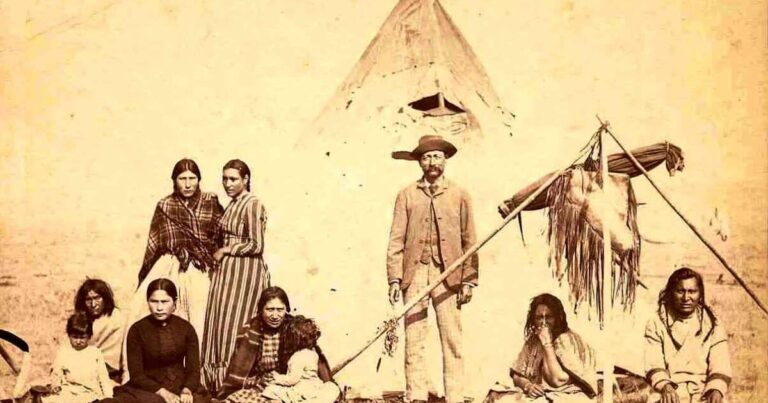

Heading Image:

Location: Fort Resolution, Northwest Territories, Canada

Credit:Canada. Department of Mines and Technical Surveys. Library and Archives Canada, PA-023095